ION

by Plato

Produced by Agora Theoria, July 2021.

Directed by Tony Tambasco

Cast

Ion .... Joseph O. Grabon

Socrates .... Jordan Gullikson

Crew

Director .... Tony Tambasco

Ion haunts me. I don't think I've ever heard and argument that Ion is Plato's most important dialogue, or even among his most important, but for anyone who works in the performing arts, it cracks the heart of what we do. Any performing arts instructor will tell you that they can't teach you artistic success, only artistic technique: but if the technique is insufficient to create success, what good is it really?

In Plato's Ion, Socrates asks the rhapsode Ion to explain the nature of his ability to perform the works of Homer exclusively, and Ion is unable to do it. If Ion performed the Iliad and Odyssey by any sort of skill, argues Socrates, he should be able to perform the works of Hesiod (for example) just as easily: Ion's inability to do so testifies to the fact that he does not perform Homer by skill, but instead by divine inspiration. Ion protests this, but he is, at the end, unable to say exactly what skill it is that he has that is particular to being a performer of Homer.

Socrates isn't the best listener in this dialogue. Socrates tells Ion that, like someone possessed at a religious festival, Ion is completely taken out of himself when he is in the middle of performance, and Ion protests the point – he is always partially in control of his performances, and has to be in order to tailor his performance for a specific audience if he wants to get paid, but Socrates glosses over this and continues to push his thesis that Ion can't possibly be in control of his actions.

Admitting the performer has any conscious control over the performance admits the possibility that performers may be skilled rather than inspired, and Socrates is too in in love ("inspired," to use the language about love that Socrates uses in Symposium) with his theory to fully consider or comprehend what Ion is telling him.

The genesis of our current approaches to theatre are in approaches developed from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Most notably, Konstantin Stanislavsky sought to create a system for average actors to use for creating performances on the same level as Eleanor Duse without her natural (or supernatural) gifts. We have been following in his footsteps ever since because his basic approach is more successful more often than the previous systems of apprenticeships that focussed on copying the work of a master actor, and perfecting the performance of certain types of characters in broad strokes.

Yet we still can't teach someone artistic success. Here I need to qualify that I don't mean professional success only, but rather the ability for any one to follow a system of actor training, practice the lessons diligently, and being able to apply their training in a predictable way to create a predictable result in the same way that we expect other skilled professionals to do (like physicians or drivers, to use some of Socrates' examples from Ion). While artists are used to thinking about artistic success as different from professional success, if artists are skilled professionals on the same order as physicians and drivers, shouldn't professional success naturally follow from artistic success? Is artistic success, as differentiated from professional success as a theatre artist, effectively a participation trophy we give ourselves for not making more money?

And, moreover, do theatre artists do ourselves a disservice in talking about our work in spiritual terms? The experience of seeing a play is often described as "church," or "communion," and practitioners often speak of the "magic" that takes place in rehearsals. We talk less about the psychological processes of creating empathy, the hours of rehearsal to thoroughly understand a dramatic text and create nuanced interpretations of it, and the other technical aspects of our craft, I think, because like Ion, we rather like the idea that there is something holy about what we do.

The muses, of course, do not actually exist. Where Stanislavsky may have democratized the profession of acting, wealth, privilege, and access have taken the place of the holy touch of the muses in determining successful professional outcomes. Very often, whether you get a job depends on whether you've made friends with a producer (or artistic director), and your ability to do that usually depends on whom you're already friends with. Thinking about the work of performance in spiritual terms keeps us from considering Ion's crucial point — that he is both in conscious control of his performance as well as emotionally affected by it — and the ways in which we have (or don't have) control over our own artistic and professional destinies. And, critically, the ways in which we can (should?) demand that our unions and professional support organizations do a better job of negotiating approaches to work that ensure opportunities are open to those outside of the old friends' network.

Most scholars view Ion as Plato's rebuke of the value of poetry to society, and while I think they're at least partially wrong, Ion continues to provoke questions about the ways that we think about our work, perhaps in ways that no contemporary performer of Plato's could have understood. It has been my privilege and pleasure to consider some of these questions with Joe and Jordan as I've directed Agora Theoria's production of Ion, and I hope you'll join us for our performances to share in the conversation.

originally published at modernphilologist.blogspot.com/2021/07/why-ion-still-matters.html

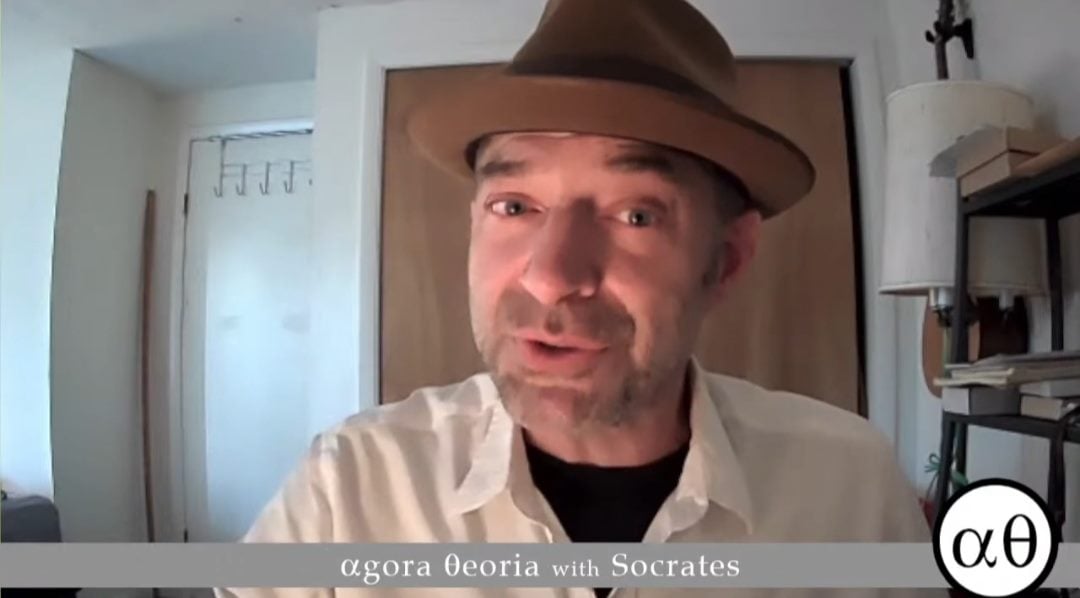

Jordan Gullikson as Socrates (left) and Joseph O. Grabon as Ion in Ion by Plato. Directed by Tony Tambasco.

Jordan Gullikson as Socrates (left) and Joseph O. Grabon as Ion in Ion by Plato. Directed by Tony Tambasco.

This is a recording made from Agora Theoria's 18 July 2021 performance of Ion.